Research Themes

Ph.D. Research

Predicting Impacts of Species’ Range Shifts

Climatic warming is causing species to undergo broad-scale geographic redistributions across virtually all systems and taxa. These “range-shifts” typically occur toward higher latitudes (i.e, poleward), toward higher elevations, or - in marine systems - toward greater depths. Though range shifts may facilitate biodiversity preservation on a global scale, they may also negatively impact recipient populations and communities via novel interspecific interactions. Early research suggests that the impacts of these neonative species on recipient populations and communities are comparable to impacts caused by human-driven invasive species. However, there are currently no frameworks for proactively predicting the impacts of neonative species.

Therefore, my current research focuses on developing frameworks that can be used to predict the impact of neonative species on recipient populations and communities prior to (or during) expansion. To do so, I am (1) conducting a regional-scale manipulative field experiment, leveraging the expansions of two intertidal predators, the whelks Acanthinucella spirata and Mexacanthina lugubris (pictured below: Acanthinucella left, Mexacanthina right), to test impact predictions derived from invasion biology theory, and (2) conducting a global-scale meta-analysis to apply the EICAT risk-assessment framework to neonative species.

Products:

Beshai and Sorte. A General Framework for Predicting the Effects of Marine Range-Expanding Species Worldwide In Prep.

Beshai et al. Applying invasion biology frameworks to predict impacts of range-expanding predators. In Review at Ecology

Suen et al. (2025). The Impact of a Range-Shifting Predator Is Affected by Prey Preference and Composition

Waite et al. (2023). Demography across latitudinal and elevational gradients for range-expanding whelks.

Data: Intertidal community survey data can be downloaded from BCO-DMO: https://www.bco-dmo.org/dataset/935622

Collaborators (Alphabetically): Paul E. Bourdeau (California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt), Lydia B. Ladah (Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico), Julio Lorda (Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Mexico), Cascade J.B. Sorte (Advisor, University of California, Irvine), Kyle J. Suen (University of California, Irvine), and Heidi Waite (currently at California Ocean Science Trust)

Interactions Between Invasive Species

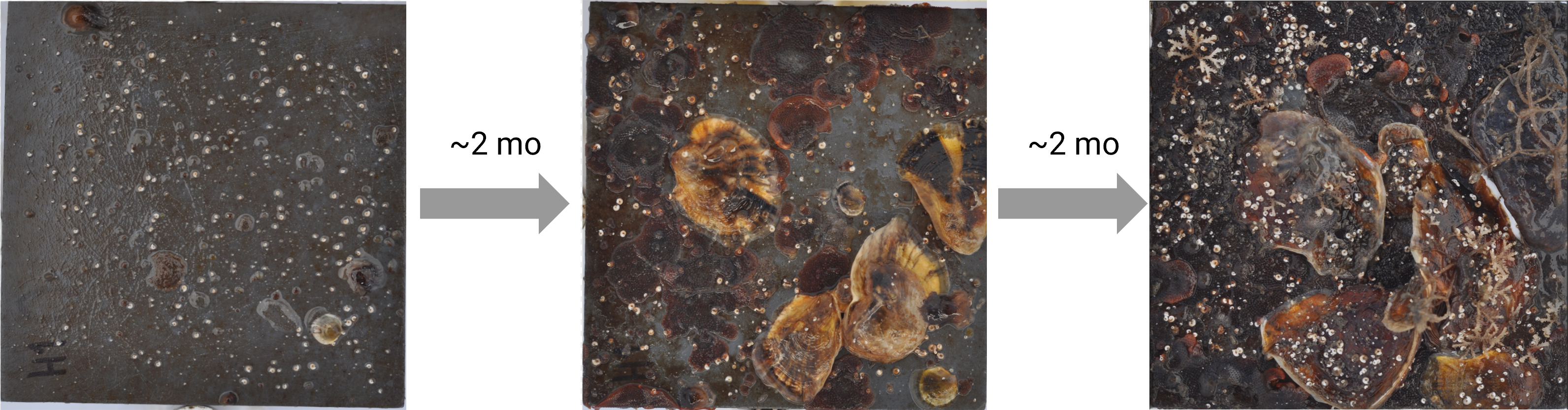

The global rate of establishment of human-driven exotic species is increasing, with few signs of slowing. The impacts of invasive species can be tremendous - estimated to directly or indirectly drive up to 60% of documented extinctions, with human-related costs exceeding $423 billion globally in 2019 - so it is critical to understand factors that promote or impede future invasions. While invasion theory holds that community diversity is a critical factor in modulating invasion success, prominent hypotheses occasionally make diverging predictions. For example, the biotic resistance hypothesis holds that species rich communities are more resistant to invasion than species-poor communities due to greater interspecific competition while the invasional meltdown hypothesis proposes that greater diversity of exotic species increases invasibility due to facilitative interactions between established exotic species. In this project, I compared predictions made by the biotic resistance and invasional meltdown hypotheses by tracking the assembly of fouling communities and abundance of exotic species in southern California.

The development of a fouling community over approx. 4 months

The development of a fouling community over approx. 4 months

Collaborators (Manuscript Order): Amy K. Henry (University of California, Irvine), Danny A. Truong (University of California, Irvine), and Cascade J.B. Sorte (Advisor, University of California, Irvine)

Scientists in Parks (via National Parks Service)

Assessing Community Change over Time

A primary directive of the National Parks Service is to protect and conserve natural resources for the enjoyment of future generations. Management of resources in parks, however, is often complicated by high visitation rates. In 2020, for example, over 350,000 individuals visited Cabrillo National Monument’s rocky intertidal communities. So how does a highly visited park such as Cabrillo National Monument ensure that its management practices are effective? As a Scientists in Parks natural resources intern, I used long-term survey data to examine changes in intertidal community composition across sites representing a gradient of human use and compared changes in Cabrillo National Monument to other high- and low-visitation sites in southern California.

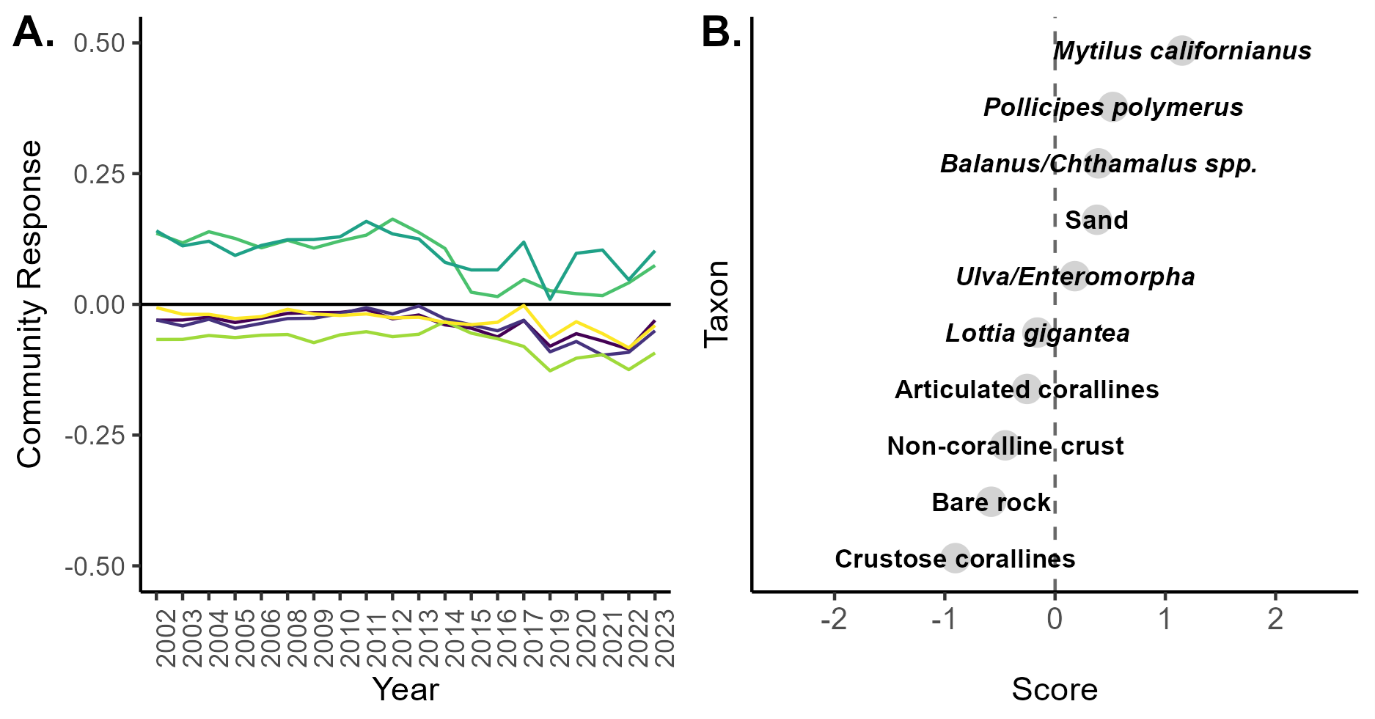

(A) A Principal Response Curve plot, visualizing changes in intertidal communities over time across sites in southern California. Different sites are different lines, and change in community composition is assessed relative to a baseline (the black horizontal line). (B) Species weights show which species/classifications have the strongest positive or negative correlations (i.e., are the drivers) of the observed patterns. For example, when a line trends up, species with a positive weight tend to increase in abundance, while species with negative weights tend to decline (and vise versa when lines trend down).

(A) A Principal Response Curve plot, visualizing changes in intertidal communities over time across sites in southern California. Different sites are different lines, and change in community composition is assessed relative to a baseline (the black horizontal line). (B) Species weights show which species/classifications have the strongest positive or negative correlations (i.e., are the drivers) of the observed patterns. For example, when a line trends up, species with a positive weight tend to increase in abundance, while species with negative weights tend to decline (and vise versa when lines trend down).

Products: Coming soon!

Collaborators (Manuscript Order): Lauren M. Pandori (National Parks Service), Taro Katayama (National Parks Service)

Earlier Research

Apparent Competition

The importance of direct competitive interactions in controlling population sizes is well-described for many plant and animal communities. Among phytophagous insects, however, there is little consensus in the importance of direct - and particularly indirect - competitive interactions. As an undergraduate in the Murphy Lab, I therefore examined the role of apparent competition (i.e., competition mediated by a shared enemy) using two species of generalist phytophagous insects (Fall Webworms, Hyphantria cunea, and Eastern Tent Caterpillars, Malacosoma californicum) in Colorado.

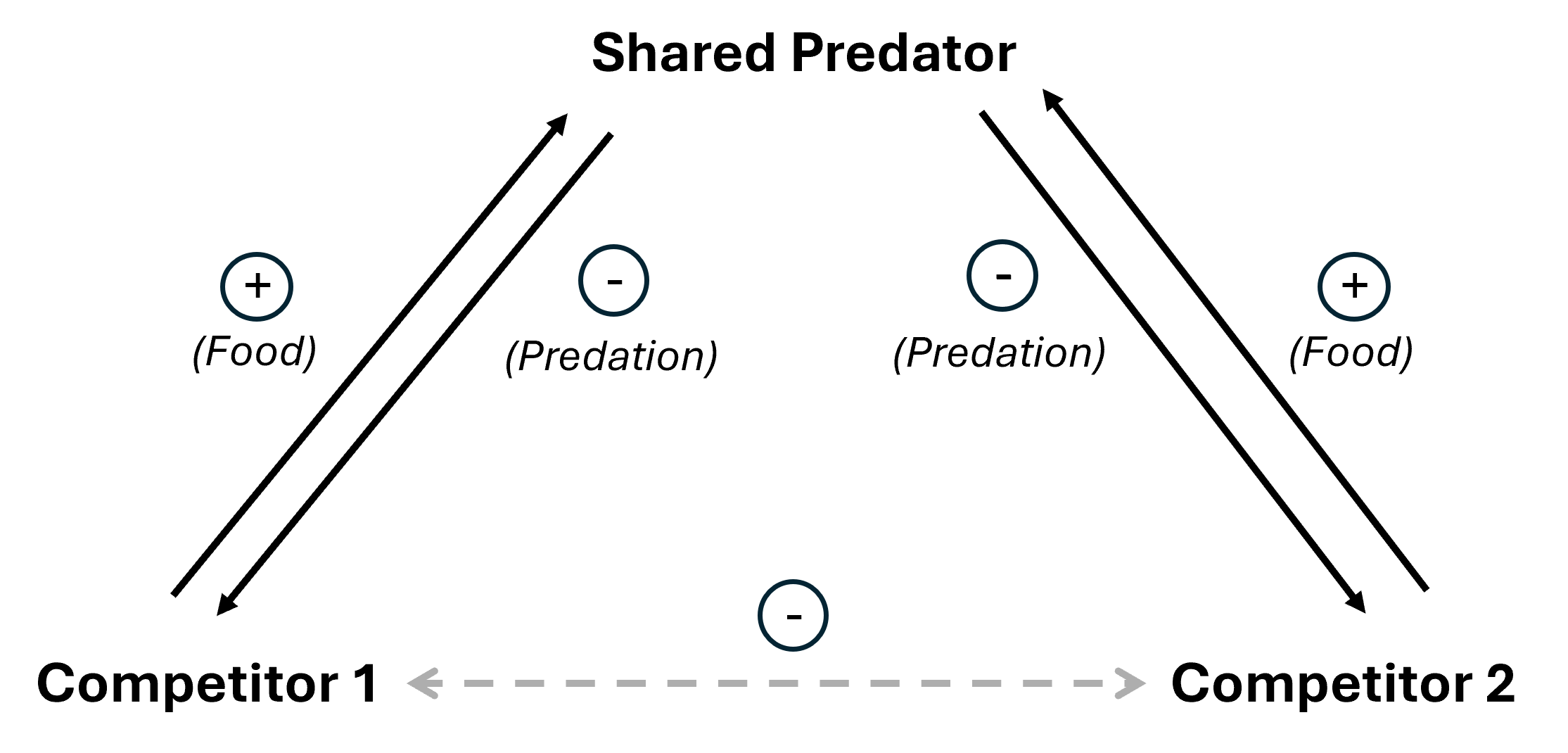

In the diagram above, direct interactions are shown using solid black arrows, while the indirect interaction (apparent competition) is shown using a dashed grey arrow. Prey species therefore “compete” by increasing predation pressure by a shared enemy (or enemies) on each other.

In the diagram above, direct interactions are shown using solid black arrows, while the indirect interaction (apparent competition) is shown using a dashed grey arrow. Prey species therefore “compete” by increasing predation pressure by a shared enemy (or enemies) on each other.

Products: The role of enemy-mediated competition in determining the fitness of a generalist herbivore

Collaborators (Manuscript Order): Elizabeth E. Barnes (Purdue University), Shannon M. Murphy (advisor, University of Denver)

Other (Non-Author) Scientific Contributions

U.S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center

The San Francisco Bay Estuary provides critical habitat for a wide range of ecologically and commercially important species but faces substantial anthropogenic pressures. Extensive diking, draining, and dredging has transformed the estuary from a tidal marsh–dominated landscape into one primarily characterized by open water and managed ponds. This large-scale alteration resulted in the loss of approximately 77% of historical wetland habitats, fundamentally reshaping the structure and function of estuarine food webs. Benthic invertebrate communities, which serve as key prey for native fishes such as the endangered Delta Smelt (Hypomesus transpacificus) and for migratory waterbirds, are likely to be particularly affected by these changes. Yet, it remains uncertain how these communities—and the energy pathways they support—will respond to ongoing restoration of tidal marshes and other ecosystem-scale interventions across the Bay. Therefore, as a Biological Science Technician at USGS, I led and supported projects that sought to answer questions about the health of these critical prey communities, including:

- Can the restoration of degraded saltmarsh habitats help recover energy pathways that support native fishes?

- How does periodic marina dredging affect the abundance of key prey taxa and the composition of benthic communities?

I didn’t author but that I contributed to: